Subscribe to the new Harvest newsletter for our latest reporting on agriculture and the environment, behind-the-scenes exclusives, and more.

A pontoon boat loaded with scientific equipment motored across a small lake lined with homes in central Missouri in December, with scientist Rebecca North onboard in a full-body orange flotation suit.

“I love being out in the field and we don’t get to go out as much as we like,” said North, an associate professor in the School of Natural Resources at the University of Missouri and director of the Mizzou Limnology Lab.

The team has been running a series of water quality tests to get an overall idea of the health of this private lake.

North has studied aquatic ecology and water quality for more than two decades. But on this day something was different: for the first time, North was being paid by a private homeowner’s association.

She lost federal funding for multiple projects last year, and is now looking for new ways to cover research costs.

“Currently, for the first time in my scientific career, I have a GoFundMe or donation button on my website,” North said.

Across the central U.S., scientists say they have experienced a year of change and uncertainty under the second Trump administration.

In the last year, the Trump administration had far-reaching negative impacts on American science, according to interviews with 14 scientists in eight states who work across a wide swath of research fields, including academic institutions and federal agencies.

They say the White House has rapidly reshaped U.S. research in three key ways: the administration slashed the federal scientific workforce, canceled thousands of federal research grants and clamped down on specific subjects like climate change and environmental justice.

In response to a request for comment from Harvest Public Media, White House spokesman Kush Desai defended the administration’s record on science.

“The United States is home to the largest public-private ecosystem of innovation in the world, and the American government is the largest funder of scientific research,” Desai wrote in a statement. “The Trump administration is committed to cutting taxpayer funding of left-wing pet projects that are masquerading as ‘scientific research’ and restoring the American people’s confidence in our scientific and public health bodies that was lost during the COVID era.”

Canceled grants and projects

The administration terminated more than 7,000 grants in the last year administered by the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation and Environmental Protection Agency alone, according to a tracker run by the watchdog group Grant Witness. This is an incomplete picture, however, as many other federal agencies also provide research grants and are not represented in the data, including the Departments of Agriculture, Energy and the Interior.

Some scientists lost more grants than others, like Bonnie Keeler, the director of the Water Resources Center at the University of Minnesota.

In the last year, Keeler had three major federal grants terminated, totaling more than $14 million. The largest was for a technical assistance center to help communities apply for federal funding for renewable energy and environmental projects. Another was a grant to support graduate student training. And the third was a grant to assess the costs of proposed water quality programs along the Mississippi River.

“It's been really, really tough, I'll be honest,” Keeler said. “It's been hard and emotional, and it sometimes is really frustrating.”

Keeler said each grant was terminated abruptly, giving her no advanced warning or opportunity to wind down the work.

“There was very little information given in these termination notices that we received via email, usually on a Friday afternoon,” she said.

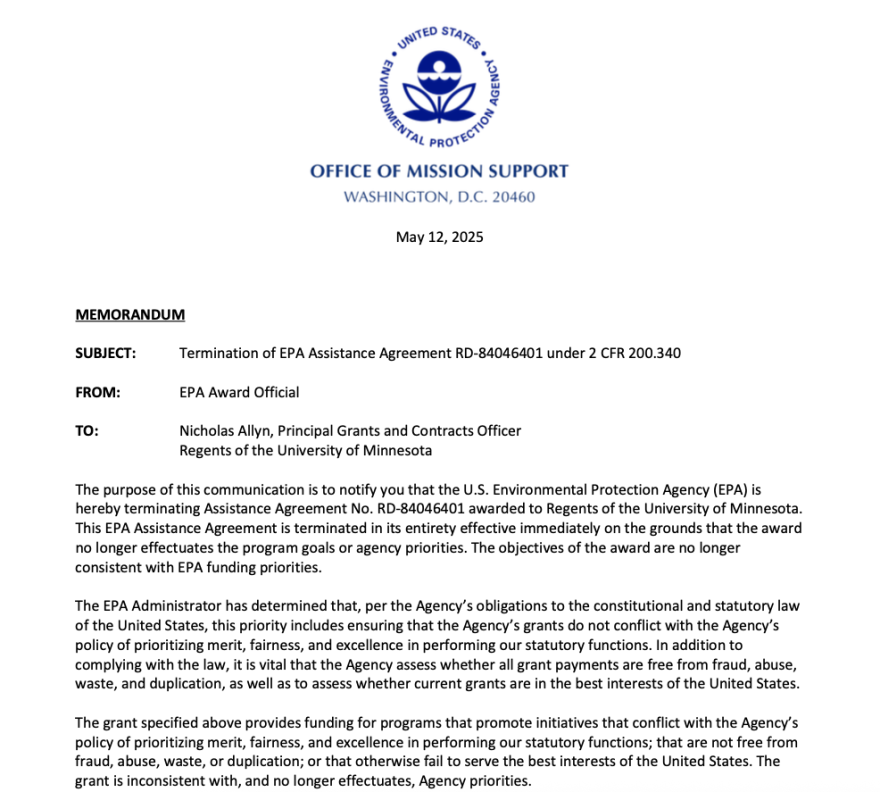

In termination letters Keeler shared with Harvest Public Media, EPA officials wrote that “the award no longer effectuates the program goals or agency priorities.” One letter said the EPA’s priority is to ensure grants do not support diversity, equity and inclusion or environmental justice initiatives.

Multiple scientists described receiving similar abrupt cancellation notices with little explanation.

The administration’s actions affected more than research grants, extending to collaborative projects that the federal government has frozen indefinitely, like the National Climate Assessment and the new National Nature Assessment, a Biden administration initiative to take stock of biodiversity loss and nature’s impacts on society.

Keeler is part of a coalition of scientists working on the National Nature Assessment – and she said the work has continued, despite the loss of federal support.

“We were able to secure foundation funding to continue that effort, and that work has now continued in earnest,” Keeler said. “We are full steam ahead on producing that report, and you should expect to see a lot more efforts coming out of that group in 2026.”

The freezing of work on the National Climate Assessment will hurt the Midwest, said Trent Ford, the Illinois State Climatologist with the State Water Survey at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Ford was going to be an author on the Midwest chapter of the next report and was planning to focus in part on livestock impacts. He said without the report, national understanding of climate change won’t be tailored to local areas.

“The chapters for the different regions brought in people working in those regions, so they have a sort of an intimate knowledge of where those problems are, who is affected and what solutions are working for that region,” Ford said.

Targeted topics

In some cases, the scientists we spoke with suspected the subject of their research brought them into the federal government’s crosshairs. One scientist lost funding after their grant was listed on Sen. Ted Cruz’s database of “Woke DEI Grants.”

Others believe terms like climate change or environmental justice led them to lose funding. Under the Trump administration, agencies have flagged certain words to avoid, according to reporting from the New York Times and other outlets.

Christopher Tessum, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, was working on a project focused on air quality and environmental justice. He assumes the subject led to the cancellation notice he received, but he said he hasn’t gotten an explanation.

“I don't have the inside information about the particular process,” Tessum said. “I think the assumption has definitely always been that because it had words like ‘equity’ and ‘decarbonization’ in the title, but I don't have confirmation of that.”

Another scientist who asked to remain anonymous because he feared retaliation also believes he was caught up in the keyword search. He places some blame on the Biden administration for asking for specific terms to be included in requests for proposals, which he said politicized science and essentially put a target on certain researchers’ backs.

Keeler said the last year has been one of “policy whiplash.” One of her canceled grants was directly related to Biden-era initiatives to support disadvantaged communities, so she wasn’t surprised the Trump administration cut it.

But she was surprised by the termination of her other grants, which she didn’t think were political. One was in direct response to an EPA call for studies looking at the cost-benefits of water quality regulations.

“This was EPA saying we need this kind of science in order to do our work better,” Keeler said. “I think it is telling that evidence-based regulatory analysis is no longer a priority of the Trump administration.”

Federal employees have also received verbal instructions not to talk about climate change, according to a scientist currently employed at a federal agency in the Midwest who asked to remain anonymous because they were not authorized to speak publicly about the matter. The scientist said these directives are not written down, but instead trickle down from national teams.

But the federal scientist said even without a directive from the Trump administration, they have found themselves avoiding terms like climate change during public events, because it has become so polarized it can lead the audience to write off the science. Instead, the scientist tries to stick to data and how the observed changes will affect Midwesterners, focusing on things like drought and changing winters.

In Illinois, Ford said in the past, the state’s politics had largely shielded him from feeling like he couldn’t talk about climate change. But that has now changed, particularly as he collaborates on grant applications with people whose livelihoods depend on the funding.

“We're still going to do climate change research, right, but we're going to call it ‘weather extremes,’” Ford said. “You know, it feels dirty, but again, I'm not going to sacrifice somebody's ability to provide for themselves or their family over a principle of saying climate change.”

Significantly fewer federal workers

Since January 2025, more than 320,000 federal workers were either fired, retired or left their jobs early, according to the U.S. Office of Personnel Management.

Doug Kluck is one of the many scientists who left their positions in the last year. After 33 years at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, he retired because he was afraid of being fired and losing health benefits for his son, who has a disability.

“The spring was full of DOGE, the effort to get rid of federal employees under false pretenses, to be honest,” Kluck said. “And one of the ways to do that is to say, ‘Hey, listen, we can fire you for basically nothing. And if we do fire you, you're going to lose your medical benefits for the rest of your life.’”

Kluck retired early from his role as the central region’s climate services director. He said of the six positions like his across the country, five are vacant.

“So now there's less coordination and less people working on issues that could save lives, honestly,” Kluck said.

Many of the scientists interviewed for this story said the gutting of the federal scientific workforce and the loss of scientists like Kluck has also affected their work.

In Illinois, Ford said coordination with federal agencies like the National Weather Service or FEMA was especially important during state-crossing extreme events like droughts or severe storms.

“In some of those cases, the communication is zero now, and it's either because those people are gone or there are so few left that they're having to do about five times the work, and they just simply can't address everything,” Ford said.

Filling the gaps

In some cases, the work has continued, but in new ways. Kluck still organizes monthly climate webinars for stakeholders in the Midwest, much like he used to do at NOAA. The University of Nebraska has provided a digital home for those meetings, which often attract more than 100 participants from a variety of institutions.

“Although I've retired, I haven't really quit my job,” Kluck said.

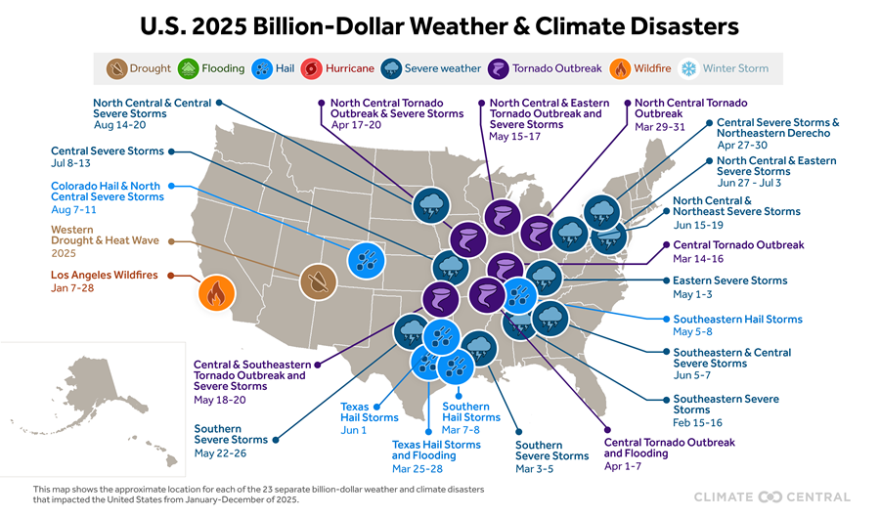

Other outside organizations have also tried to fill gaps in the last year, including Climate Central, a U.S.-based nonprofit.

“So many key parts of the climate and weather enterprise in the federal government have been decimated,” said Kristina Dahl, Climate Central’s vice president for science.

In the last year, Climate Central hired multiple former federal scientists who lost their jobs. The group also took on new tasks the federal government used to do, like holding monthly climate briefings and publishing a database of billion-dollar disasters. This month, the organization announced that the U.S. experienced the third most billion-dollar disasters on record in 2025.

But Dahl said organizations like hers won’t come close to filling the void.

“The reality is that even collectively, all of the U.S.-based climate and environmental nonprofits don't have the same capacity as the federal government,” Dahl said.

Keeler agrees. She was relieved that foundations stepped in to support the National Nature Assessment, but said the resources aren’t close to the need.

“Philanthropy at any scale is never going to be able to replicate the amount of funding that the federal government can support for core scientific inquiry and research and development,” Keeler said.

A wary future

In all, the scientists Harvest Public Media interviewed described a year of major cuts and a diminished role for American science in the world.

“A lot depends on the American scientific endeavor in general,” Tessum at the University of Illinois said. “It's a big engine of economic progress in the United States. It's a big reason why people talk about American exceptionalism.”

It has also been a demoralizing year, the scientists said.

“You put so much of yourself into these projects, and you do it because you know that it matters,” Keeler said. “You know that the research can have an impact. You've seen it have an impact. And so, to lose that is really tough.”

Rebecca North of the University of Missouri is Canadian and came to the U.S. on an H-1B visa. She has been thinking about a similar period in her country’s history that happened more than a decade ago, when scientific funding was also cut and thousands of Canadian federal scientists lost their jobs.

“That's the one positive message I can at least give to students is, we know that countries and programs can come back from things like this,” North said. “Canada is a great example of that.”

In the meantime, she added, regular people can look for local citizen science programs to participate in, to try to continue research and data collection.

While the last year has felt a little like “the dark ages” to Doug Kluck, he doesn’t think it will last.

“You can downplay climate change all you want,” Kluck said. “You can call it something else. It doesn't really matter. We're all going to be affected by it, whether we like it or not. And I'm not saying this is a belief system. This is a pure science and physics issue.”

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest and Great Plains. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.