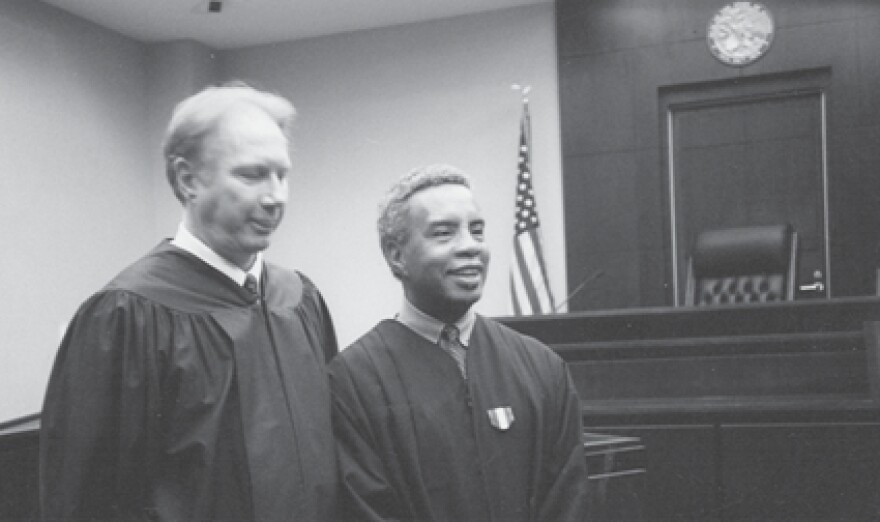

Walter Braud was the first Black prosecutor in Rock Island and a criminal defense trial lawyer for 27 years. He was also the first Black circuit judge in Western Illinois and only the second Black chief judge in Illinois history. WVIK News spoke with Braud about his memoir called "Bessie's Prayer."

The transcript has been edited for clarity.

WVIK News: Thank you so much. And kind of going through my list here, can you start by telling me how, why did you decide to write a book?

Walter Braud: Well, I was at the end of my legal career, which was 50 years long, when I came to Rock Island in 1969. It's now 2019, and I had been the chief judge for five years. That, surprisingly to me, came along with the duty and the blessing of having to try to build a badly needed new courthouse that they'd been trying to build since 1955, when it was declared to be unfit for human habitation. But it was politically impossible to get done. So I was 75 years old. I was a circuit judge. I got promoted to chief judge. And I thought it was because I was a pretty good judge. But I think it turned out that I was the old guy and probably able to put up the fight and not worry so much about the collateral damages. But in any event, it was a plus-four-year, 24-7 battle that was pretty exhausting. I mean, both sides of the battle had good reasons for their position. You know, the taxpayers didn't want to build a new courthouse because it increased their taxes. And that's totally understandable. But as the chief judge and the county board, we had an obligation to build a courthouse because that courthouse was unsafe. Somebody soon was going to be involved in a Holocaust, and some people were going to be dying. And so when I found out after I was chief judge and the county board chairman, a friend of mine named Moose, called me over and said, 'Hey, big boy, you got the big job now, (knocks on table) so get ready to start the fight.' So I knew that maybe because of my past life that this was what I was born to do. So I jumped in and got some people to help me, and we built the courthouse. We opened it on December 18, 2018. Then we tried to tear down the old courthouse. That turned out to be a bridge too far. I wasn't able to get that done. I considered myself to be Mighty Mouse, and I could jump in and rescue anything, but I wasn't able to carry over that. It was a joyful battle, but at the end of it, I was exhausted mentally and physically. So I took some time off, and after about seven days, I received a message from my father who was deceased.

And the message came by way of music. I heard him playing the piano. He was a cabaret piano part-time all of his life, and I was a singer in various phases all of my life. We performed music together. He was playing on the sunny side of the street, which we knew growing up and when I went to the Irish bars with him to sing, that that was his way of saying no matter how dark the clouds are, whatever the murkiness of life, get up, you know, grab your coat, and (starts singing) 'Grab your hat, leave your worries on the doorstep. Don't forget your feet. Put them on the sunny side of the street.' So I heard that tinkle, tinkle, tinkle, and my voice, my brain inside of my head started singing. Got up, put on my clothes about 5 o'clock in the morning, went for a walk on the river, and the book was born.

WVIK News: Yeah, it was wonderful to read through this. Just so many things throughout Illinois history kind of viewing through your family's eyes. I was interested in how it was living together with your sisters and your son and his family and your parents all under one roof when you were in Chicago.

Braud: It was wonderful. You know, I was born with the, so love God and family first above all things. Be excellent and show kindness in all endeavors. And help others before you help yourselves. So that's the marching orders for everybody. And with that in mind, there are all the other little marching orders that I got from Mama. But they all sort of fall under that rubric. And so it was just a precious time when everybody's on the same page. Everybody's trying to achieve the same thing, which is love God and family first and so on and so forth.

So each child is singled out for his or her propensities, abilities. And then my mother shepherds them through. So for me it was to be an opera singer. My middle sister was to be a school teacher. My older sister was going to be a nun. And so on and so forth, depending on what my mother decided our best chances in life were. But the warmth and the love and the dedication of everybody. My parents made a pact after she knew my older sister was being born. They got together and said, she sat, my mother and grandmother. My mother sat my grandmother and father down at the table and said, here's the plan. I promised Jesus to raise these children a certain way. And I need your commitment to be a part of that. So they made a pact. They made a pact that everything for the children, nothing for ourselves until their needs are taken care of. So in that rubric, even though we were strained financially with my father being the only person with a real legitimate income. He had two jobs. My grandmother also working as a maid. We never felt poor, though we were by objective standards.

WVIK News: What was going through your head when you were coming to Rock Island to interview? For the assistant state attorney's position way back when.

Braud: I didn't realize this until I'm old and being reflective. Because I've sort of lived my life like a hurricane. Things, opportunities or things would come up and I would get fixated on them compulsively. And then I would keep doing them until they fell apart or they moved on to something else. So when I became a lawyer. And I didn't take the time to think of what I would do after I was a lawyer. So I'm in Chicago. I'm studying to be a school teacher. But I'm going to law school at night. Living in the projects and supporting my family by driving a taxi cab. And then when I graduated from, when I became a school teacher after college. I went to law school at night. When I graduated from law school. I never took the time to figure out what I was going to do afterwards.

But in my senior year I realized that, you know, I need a job. So I would talk to the other Black guys at the school. There were only about five of us in a school of about 500. And one of them was an older guy about 40 years old. Who was, he would come back to night law school so he could get a degree. So he could crack through the door. In an accounting firm where he worked. And we would visit sometimes, stopping after class to have a beer. And, you know, I would tell him, man, 'I don't know how this is going to work. You know, I'm about two years older than my classmates. I'm an average student at best. It's night school. I don't have much going for me. And I'm Black.' At a time when that was pretty exclusionary in the legal field. Sometime later. I get a phone call. I did find a job in a small little firm. That where the guy basically had me working as a file clerk taking files downtown. But at least it paid what I made as a school teacher. So I didn't lose any money. But I get a phone call. He says, 'Hey. This is', and then his name that I don't recall right now. I'd have to look in the book. But he calls and says, 'Are you still looking for a job? I'm looking for a job. He says, 'Well I think I have one for you. I'm in Moline, Illinois. At the John Deere Corporation. Representing my company at a big business conference. And I've met a guy named Mel Pettis. Pettis is a high-level Black executive at John Deere. And he says that the prosecutor here is looking for a minority prosecutor.' Because the Black citizens in Rock Island and Rock Island County had given him a lot of help in getting elected. So it was, by my mother's terms, it was God's will. A miracle. And that's, so we had a little conversation. I came out for a visit. And knew immediately that this was the place to be. As I say in the book, you only have to be here about six or seven hours. Especially if you're from Chicago. In Chicago, people are guarded. They're very wary of strangers. They don't speak to strangers. They rarely smile at strangers. And they run from you if you ask for help. Unless they accept that you look like them or feel like them. And that they're safe with you. It's not that they don't like you. Chicagoans are wonderful people. But when you're living, you know, with three million people squared into fifty square miles. It brings some tensions. So to come to Rock Island, where as I say in the book, the people are so nice that they smile and offer help. Even if they don't like you. It was just such a breath of fresh air. So when I came out for my interview, I kind of knew I had the job as soon as I got here. But still the state's attorney, "Jim" James DeWulf, in his first term, took me all around and showed me off. And we met everybody. And I could see immediately that I was going to be there. I would have a good opportunity to begin to try felony cases, which was my goal. The Catholic Church, which I needed, and a Catholic school was right next to the courthouse. You know, I just landed in a pot of jam. And it's never been different. It's just always been... The sun has always shined on me ever since I came here.

WVIK News: Kind of going back to when you were a child and your mom kind of setting out the plans for each of her kids. She mentioned that you... She wanted you to be an opera singer. How was that transitioning from singing? Because you still did that throughout most of your life in the memoir that I was reading. But professionally going into law, what was Bessie's reaction to you going, 'Hey, I want to be a lawyer?'

Braud: Well, so when I was five years old, my mother surprised me with an army uniform. The one that's shown on the cover of the book. And told me that I was going to go downtown to the Chicago Stadium and sing God Bless America. That my father was going to play the piano. And my uncle, that I didn't know, was coming in with the army band. And they were going to perform to get bonds to raise money to fight the Second World War. So that's my first introduction. So from that, my grandmother's church... She would have her friends come to the house. I think I was maybe seven years old. And they would hear me sing with my father. And they said, 'Well, you know, let Walter come and sing at the church.' It was the Protestant church. So from there, I end up at the Protestant church. In all of this, they decide, you know, you have to have some real special lessons. This boy can be in the opera. my cousin Tina, who's really my Aunt Tina, helped my mother pay for my music lessons. And I mean, it was very rigorous. I had lessons once a week. And I had to do my vocalizations and scales 45 minutes a day, five days a week. I mean, it was... I was really going to be an opera singer. And despite all of my other activities, roaming Chicago like Huckleberry Finn, as I like to say, and playing with my friends, and doing at least enough in school to get a B, I was really serious about the opera business. I didn't have to think that I was serious in my head because my mother made sure that I did what I needed to do. And so in the course of that, I was on television once. I sang on the radio four times.

And different things happened. But what really happened was when I was 13 and I reached puberty, my voice dropped. Not a lot, but enough that I couldn't hit the notes that are required of a tenor. And not low enough for me to transition to a lower range. So basically, my career as an opera singer was over. So my mother just didn't hesitate. She just plunked me into an all-boys, rigorous Catholic high school and said, you're going to be a schoolteacher. So that was fine for about a year until I became enamored of doo-wop music, which was all the rage at the time. This was before Motown, about five years before Motown. So this is early doo-wop. I'm in on the ground floor. So I quit my high school. Didn't tell my mother, of course. And went to a public high school. And then I got into a lot of fights at public high school because there was a lot of racial transition. And I wasn't happy there. But realistically, I probably wanted to quit high school because I wanted to be a doo-wop singer. But the bottom line was I did quit high school and I became a doo-wop singer. We recorded one record. As I say in the book, it flopped like a fish. But I had the experience. And we performed a few times. Once with James Brown. And so we made our record. So I had a year and a half of being a musical entertainer as my career. But my actual career was dropout. And so after about a year and a half of that, the manager had promised us a second recording. And it was going to come in October of 1957. My 18th birthday was on the horizon. And I would have been ineligible to go back to school. And of course, I'm not processing all this because I'm... well we drank wine probably every weekend with the singing group and a bunch of boys that hung out on the school steps. So for a lot of reasons, and my girlfriend... And I always had jobs. So I always had jobs, even during that time. I didn't realize it. So my mother pulled me up short and sat me down in the dining room and said, 'This is where it is. You know, you got to get back in school right away. And don't come home drunk again and singing love songs to the heavens and waking up the neighbors, not ever again.' And she said it in a way that I understood that I needed to pay attention this time, that I wouldn't have a second chance at school or with her. And so I made up my mind that I go back to school. Unfortunately, so I was going to go and say goodbye to my friends. So being in a singing group is like being in an army platoon or on a baseball team. These are my brothers. They are as close to me as skin. And now I have to go and tell them, and our fans, the people that sit around on the school steps and listen to us and see us as recording artists. Because we are recording artists. One record, of course. But by the time I got there, having stopped off for a few kisses with my girlfriend to give myself courage so I could tell my friends goodbye, by the time I got to the top step where the guys were performing, I was drunk. And I forgot to say goodbye. And we sang songs until 2 o'clock in the morning. And when I got home, my mother was waiting for me with a broomstick. Beat me on the head like a rented mule. And finished it off by saying, 'You know, be somebody or I'd rather see you dead. Go back to school.' So the next morning I got up and apologized and went back to school. And it is my nature that whatever I'm doing, it's without distraction. So from there I was off to the races. Back to high school, on to college, college become a school teacher, become a lawyer, etc.

WVIK News: Were you able to say goodbye at all to your singing group after that night?

Braud: No

WVIK News: Have you been able to keep in touch with any of them?

Braud: Not until many years later. Many years later. When we were all at the end of our adult careers. I never got a chance to say goodbye.

WVIK News: I'm going to be bouncing around the book a little bit here. But I was curious about your trip to Mexico City where you were learning Spanish at that time in person and then driving all the way back to Chicago from there. How was that experience?

Braud: When I was school teaching? So I became a school teacher and I say in the book that that was the most fulfilling job that I ever had and I still feel that way. So much so that even when I was a lawyer at age 50 I thought I'm going to get tired of this being in the courtroom under this kind of pressure and I'm going to go back to school teaching. But it never happened. But I was a school teacher and I intentionally chose a school in a devastated area of Chicago because it was not too far from the projects where I was living. Public housing projects. And it was not too far from the law school that I was going to be attending. And for those reasons it turned out that the school that I picked was in the Skid Row area. And that was the part that they made the movie about during the Great Depression when tens of thousands of men were out of work and they lived on the street and they called it Skid Row and most of them became alcoholics and eating out of food kitchens. So that's where it was and of course the Depression was over. The Second World War wiped out the Depression and brought prosperity to everyone but the neighborhood had never recovered. So it was a small industrial neighborhood on the near west side of Chicago not too far from Chicago Stadium which is now called Bull Stadium. And as it turned out, my students were all immigrants. I call them all immigrants. So we had black kids from Mississippi. Never been in the city before. Their families had never been in the city before. They're all coming for a better life. Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, Spanish speakers and white kids, country, hillbillies more or less from West Virginia in almost equal numbers. And I just thought 'Wow this is going to be great.' You know it's in my blood because my great great grandmother was a school teacher in a one room school house in Mississippi and she passed that on to her daughter who wasn't able to get a college education but she passed it on to her daughter who was my mother who made it all the way to her senior year before the Great Depression threw her down on the ground and now it's passed on to me. This creativity. So I found out all of these ways to allow these children to come to know each other as people I say in the book after a few months a response to a question might come from a hillbilly accent or a country accent or a Mississippi accent or a Spanish accent and everybody just rolled on. Everybody just rolled on.

But I became infatuated with the Spanish language and I think it's because of all the Latin I had when I was in Catholic school and so I kept trying to improve myself. I'd go to the local markets and buy things I didn't need. I'd talk to people on the street that didn't know why I was talking to them. I'd go to Spanish movies. I'd listen to the radio. But I wasn't getting it enough and I could see by the migration standards that whether I was going to be a school teacher or become a lawyer that I needed to learn how to speak Spanish. Well enough to function. So in 1966, I'd been teaching for two years. I had enough money and I bought a new car. Still living in the projects. And I got a fraternity brother friend of mine and we just signed up at the University of Mexico in Mexico City and off we went. And we took an eight week course but after six weeks I figured I'd learned about as much as I needed to know and we just said to ourselves 'Once we cross Laredo, Texas we don't speak English anymore. Unless we have to. Even to each other.' And so we were silent a lot (laughs). But you know we went to dinner and we went to our classes and we just mingled as much as we possibly could. We rented an apartment hid the car in the back covered it over and didn't use it again. At the end of six weeks it just struck me. I'm not sure I was just home sick. But it's time to go home. So back we came. And as I had hoped from then on I was really able to speak Spanish. I mean, I'm not grammatically correct. I certainly couldn't write anything like this book. But I can get about 90% of what everybody's saying and I can say about 75% of what I want to say. And certainly more than enough for my kids. And has served me remarkably well in my legal practice. I mean more than one case I was able to save somebody because of my fluency in Spanish.

WVIK News: I know I don't want to take up too much of your time today. But I was curious. You mention in the book about one of your sisters dealing with mental illness in her life. And I was wondering how that experience in your family have kind of affected your rulings as a judge for any cases that would deal with individuals who may have a mental illness.

Braud: I have a deep sympathy for people with mental illness. So my older sister Barbara I think probably was drifting into schizophrenia maybe when she was 13 years old when she punched a nun in the face at the Catholic high school. She misinterpreted my mother's instructions that we children should always remember to protect one another. And that if somebody was to attack one of us they were attacking all of us. And so the nun was sort of challenging my middle sister who didn't want to eat her lunch because it was split pea soup and she just hated split pea soup. And the nun was saying 'You must eat your split pea soup. There are starving children in Africa and starving children in China.' Bam! She hits the table. My older sister sees this and before the nun could do another blam on the table and another insistence about eating her split pea soup she punches the nun in the face. And so she didn't get expelled and I can only imagine it's because my mother and the priest at the school and the nuns this was an all Black school. The only white person at the school was the priest. That's why the subtitle is only the priest was white. But Father Ryan didn't expel her and so it was only a few years later that I began to understand from my mother that Barbara had a problem. And then I watched my mother love her, follow her wherever as her problems worsened she ended up in a hostile abusive marriage where she was beaten and hospitalized all of which just blew it all up. The first thing that blew it up was that she wanted to be a nun and the local school, our school Holy Cross the nuns there recommended her to go to Loretta Academy where you go to high school to become a nun, but they weren't accepting Blacks and so she couldn't get in and I think that sort of twisted the nail a little more but that's just speculation. But by the time I was in my late teens and starting college she was really in trouble and then she married poorly and then it exploded and then there was a series of hospitalizations for the rest of her life and my mother just patiently, doggedly would go to see her take care of her, talk about her try to understand her so as I got older that fell to me as my father who had Parkinson's and had to retire early and then died in 1977 and my mother got older and couldn't drive to these distant places especially when she moved to Rock Island and the hospital was in South Chicago so I took that over and when I would go there I would, I learned after a few visits not to argue with my sister to allow her to be whoever she was at that given moment and it could be a different person. I mean the same person with the same facts but a completely different story and I learned that mentally ill people are not liars that they tell truth and I learned that not only from listening to her but from listening to other patients that were there who would always see me coming and want a mooch of dollar off of me or cigarettes, but the trade off was that they had to talk to me for five or ten minutes and I just had such sympathy so that when I was in my legal practice my private legal practice there were a group of mentally ill people walking the mall in front of the of our office building and there was a mental health facility, small office nearby and then a bigger one farther on but they would parade around in various states of medication and I would go out of my way to be kind to them say hello and acknowledge them as human beings some of them were mooching, some were not and so that's how I got into the kindnesses with them

And so Larry Lowe is the story I tell but he's symbolic of others but he's the one that I talk about that is so memorable because he was such a memorable character. If he wasn't mentally ill he would have been a great comedian he would just absolutely fall down on your knees laughing comedian except he wasn't; he was a person and so that empathy for people with mental illness helped me in so many ways because I helped him it brought me to Margaret Kinion who suffered in my opinion from split personality which was one of the biggest cases I ever had even though I didn't win it, but because I represented her and presented as effectively as I could her defense of split personality my business exploded just beyond anything I could have possibly imagined and so all of these links just kind of continued and so that's kind of how that worked so I had that empathy always and still do.

WVIK News: Was there a part of this book that really stayed with you? When you were writing it - did the memories kind of come back? You had to take maybe a few days to kind of handle all of that before going back and finishing a certain chapter or life event?

Braud: I think the epilogue where my mother has taught me how to live and now she's teaching me how to die - that story and then probably the stories of my childhood - the Mighty Mouse story when I went to the theater - the fist fights in the neighborhood and meeting Gertrude those stories can weep me up every time.

WVIK News: You mentioned your dad had a hand in you writing this book speaking through you through music - have you heard from your mom in any of the years since she passed? Has she kept in contact with you from beyond?

Braud: I'm not sure if I don't share my sister's mental illness, but I have always been in touch with my mother, my father, and my grandmother throughout my childhood years, being warned in danger from my grandmother when she's eight miles away or even dead. My father waking me up to tell me to get off my lazy butt and get busy doing something worthwhile as my mother says 'You can stay busy until God takes your breath away' and that's why I have this book. My father and my grandmother and my mother -my mother had all of these wisdoms that she would put on me and they sort of enveloped my thinking unconsciously and they're always there they're still there so when I'm weary for instance and I think you're 85 years old for God's sake give it a rest just sit on the couch like any other normal human being would do and watch the television you know let Kamala Harris worry about the world just look at a western but I can't do it because my mother's in the back of my head going 'You're not dead, you're still breathing get up, get busy', so all of these communications have lived with me always my father I think my father's greatest gift was to be productive every day, not complain about anything and to be kind. My mother taught kindness but my father showed it always. He'd come back from work where he was a janitor eventually the head maintenance guy had a big YMCA pretty big job for a Black guy back then and maybe he had to stay two hours over to be a janitor because the real janitor got drunk at lunch and passed out and he'd come back and he'd fuss a little bit and I'd say well did you fire him 'Oh god fire him he's got a family' I said 'But dad he's worthless' he says 'He's not worthless he's only drunk every now and then' but that was his attitude to everyone and so when I would deal with other people if someone would come to me and say 'Oh Mr. Judge Braud, Lawyer Braud, I've got this problem' okay well we'll see if we can help you 'Well what's it going to cost' 'Well it's going to be $500' 'I don't have $500' I said 'Don't worry about'. 'What we're going to worry about is seeing if we can fix your problem and then we'll worry about how you can pay me or if you can pay me will that work?' so it's formed me these relationships and my sisters and my brothers and that's why there's 22 of us all linked together still living you know of course this involves the wives and husbands and nieces and nephews but till death.

WVIK News: and since you finished with the book you're going to be spending your time hanging out with them more often or another book in the making if your mom's wanting you to not sit on the couch?

Braud: Well we have a big Thanksgiving everybody's coming home from all over the country so we'll have probably all these 22 people around here, but then I'm going to ride the horse I'm on which is promoting this book with the help of my publicist here Jason and we'll see how far the horse runs and when he gets tired out and decides to lay down and rest then I'll start the next book.

WVIK News: Sounds good and with that Walter, that's all the questions I have for you today.

Braud: Thank you, thank you for your kindness.

Walter D. Braud's memoir "Bessie's Prayer" is now available.

This story was produced by WVIK, Quad Cities NPR. We rely on financial support from our listeners and readers to provide coverage of the issues that matter to the Quad Cities region and beyond. As someone who values the content created by WVIK's news department, please consider making a financial contribution to support our work.